Complex tapestries intertwine Peruvian tradition and a contemporary aesthetic

by D. WOOD for Fibert Arts Magazine

Ann Hamilton, one of Americas most distinguished sculptors, has said, “Cloth is an accumulation of many gestures of crossing.” Elementally, she was referring to the countless times weft intertwines with warp as a fabric comes to life. Yet, in the hands of a master weaver, the crossings are not only technical: they can be historical, cultural, social, and even metaphysical. Maximo Laura, Peru’s preeminent tapestry artist/designer, is responsible for cloth composed of multilayered crossings.

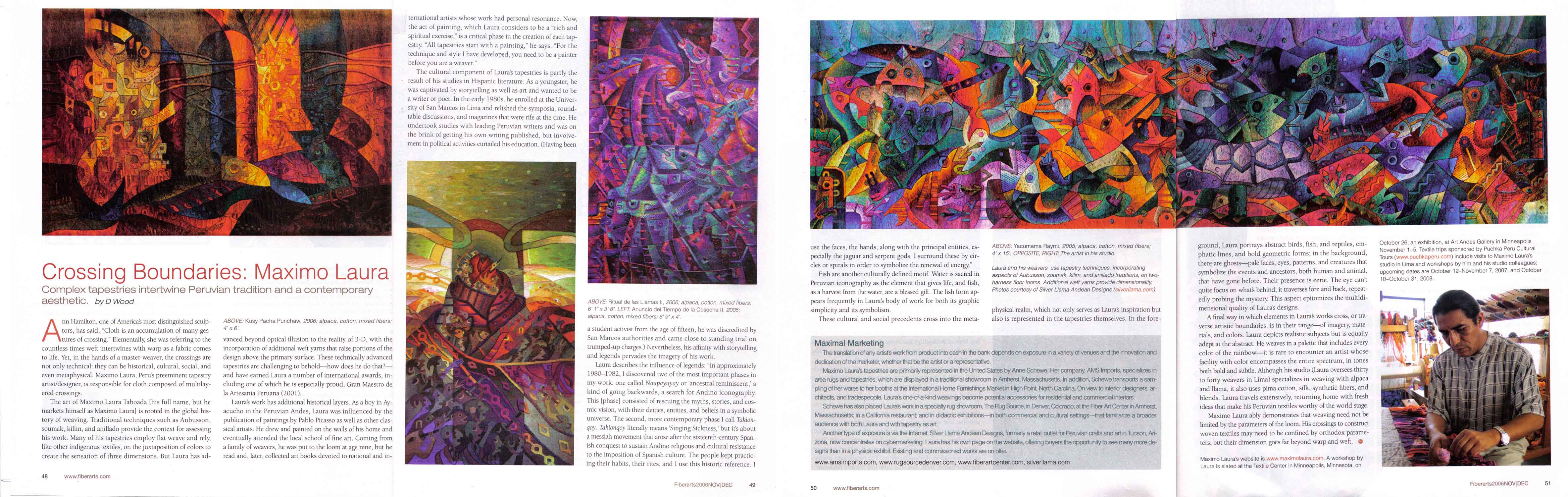

The art of Maximo Laura Taboada [his full name, but he markets himself as Maximo Laura] is rooted in the global history of weaving. Traditional techniques such as Aubusson, soumak, kilim, and anillado provide the context for assessing his work. Many of his tapestries employ flat weave and rely, like other indigenous textiles, on the juxtaposition of colors to create the sensation of three dimensions. But Laura has advanced beyond optical illusion to the reality of 3-D, with the incorporation of additional weft yarns that raise portions of the design above the primary surface. These technically advanced tapestries are challenging to behold—how does he do that?— and have earned Laura a number of international awards, including one of which he is especially proud, Gran Maestro de la Artesania Peruana (2001).

Laura’s work has additional historical layers. As a boy in Ayacucho in the Peruvian Andes, Laura was influenced by the publication of paintings by Pablo Picasso as well as other classical artists. He drew and painted on the walls of his home and eventually attended the local school of fine art. Coming from a family of weavers, he was put to the loom at age nine, but he read and, later, collected art books devoted to national and international artists whose work had personal resonance. Now, the act of painting, which Laura considers to be a “rich and spiritual exercise,” is a critical phase in the creation of each tapestry. “All tapestries start with a painting,” he says. “For the technique and style I have developed, you need to be a painter before you are a weaver.”

The cultural component of Lauras tapestries is partly the result of his studies in Hispanic literature. As a youngster, he was captivated by storytelling as well as art and wanted to be a writer or poet. In the early 1980s, he enrolled at the University of San Marcos in Lima and relished the symposia, round-table discussions, and magazines that were rife at the time. He undertook studies with leading Peruvian writers and was on the brink of getting his own writing published, but involvement in political activities curtailed his education. (Having been a student activist from the age of fifteen, he was discredited by San Marcos authorities and came close to standing trial on trumped-up charges.) Nevertheless, his affinity with storytelling and legends pervades the imagery of his work.

Laura describes the influence of legends: “In approximately 1980-1982, I discovered two of the most important phases in my work: one called Naupayuyay or ‘ancestral reminiscent,’ a kind of going backwards, a search for Andino iconography. This [phase] consisted of rescuing the myths, stories, and cosmic vision, with their deities, entities, and beliefs in a symbolic universe. The second, more contemporary phase I call Takion-qoy. Takionqoy literally means ‘Singing Sickness,’ but it’s about a messiah movement that arose after the sixteenth-century Spanish conquest to sustain Andino religious and cultural resistance to the imposition of Spanish culture. The people kept practicing their habits, their rites, and I use this historic reference. I use the faces, the hands, along with the principal entities, especially the jaguar and serpent gods. I surround these by circles or spirals in ground, Laura portrays abstract birds, fish, and reptiles, emphatic lines, and bold geometric forms; in the background, there are ghosts—pale faces, eyes, patterns, and creatures that symbolize the events and ancestors, both human and animal, that have gone before. Their presence is eerie. The eye can’t quite focus on what’s behind; it traverses fore and back, repeatedly probing the mystery This aspect epitomizes the multidimensional quality of Laura’s designs.

A final way in which elements in Laura’s works cross, or traverse artistic boundaries, is in their range—of imagery, materials, and colors. Laura depicts realistic subjects but is equally adept at the abstract. He weaves in a palette that includes every color of the rainbow—it is rare to encounter an artist whose facility with color encompasses the entire spectrum, in tones both bold and subtle. Although his studio (Laura oversees thirty to forty weavers in Lima) specializes in weaving with alpaca and llama, it also uses pima cotton, silk, synthetic fibers, and blends. Laura travels extensively, returning home with fresh ideas that make his Peruvian textiles worthy of the world stage.

Maximo Laura ably demonstrates that weaving need not be limited by the parameters of the loom. His crossings to construct woven textiles may need to be confined by orthodox parameters, but their dimension goes far beyond warp and weft.

Learn more about Maximo Laura

Hand/Eye Magazine

Maximo Laura was recently designated as one of Peru’s Living Treasures, an honor worn easily by this self-taught artist whose textiles have received numerous …

Fiber Art Now Magazine

In many villages throughout Peru, time has stopped. Indigenous people proudly wear traditional clothing that identifies their specific region and community …

Wild Fibers Magazine

In a culture with a spectacular, centuries-old tradition of textile production, the tapestries of Maestro Máximo Laura stand out from the rest. Máximo Laura’s …

Textile Forum Magazine

The following text summarises the content of two conversations I had with Maximo Laura in Costa Rica between 10th and 13th September of this year …