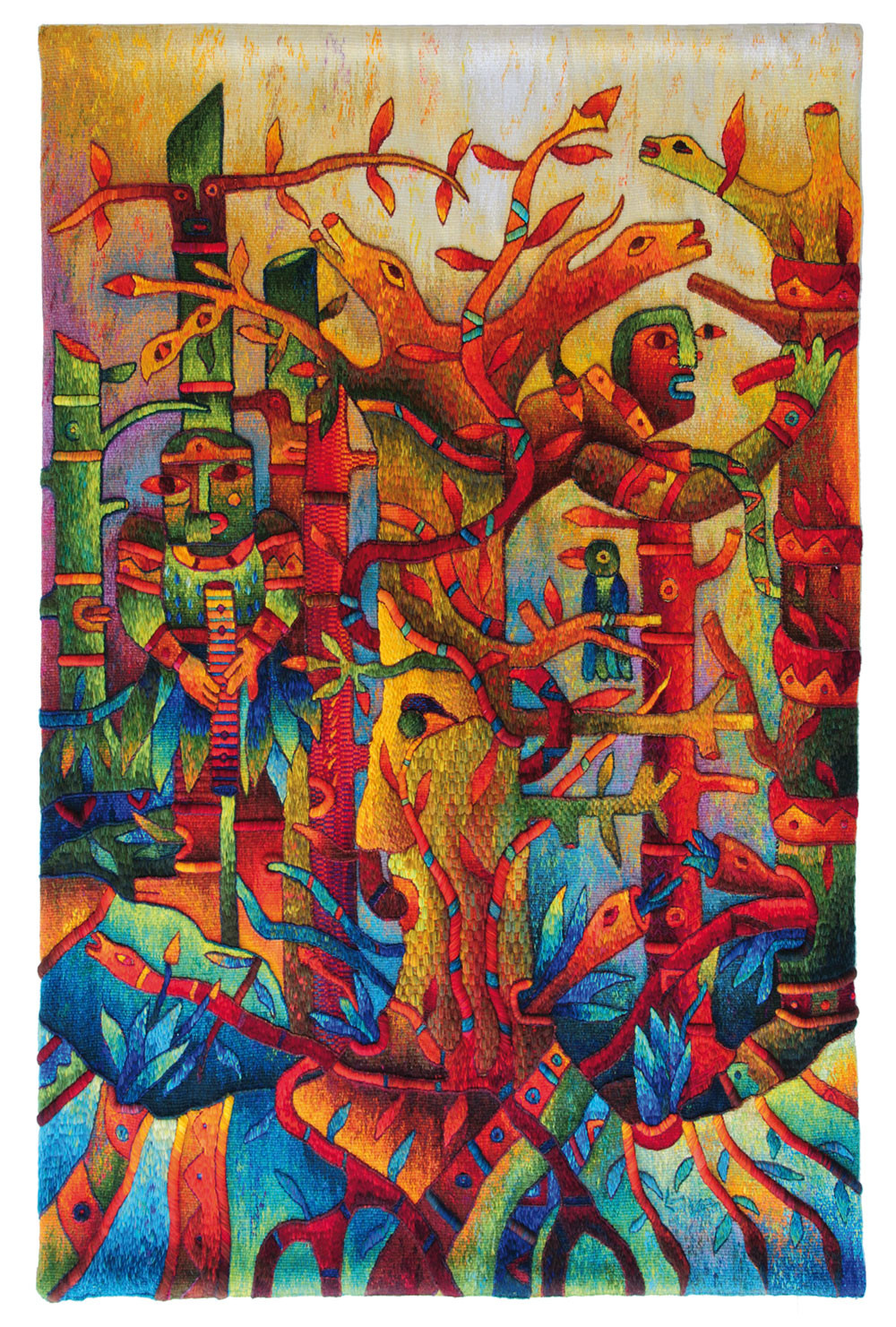

Obsessive … Feverish … Intense …

Maximo Laura’s distinctive style provides a bold Interpretation of Andean Art

Story by Ellie Kemp Photo by Linda N. Cortright

Why is Maximo Laura’s work so dramatically different from that of his peers? Why did he quietly reject the traditional aesthetic of his people and forge a style of his own? Was it something in his upbringing? Something about the culture? Providence? Perhaps it was a combination of all three. Growing up amid yarns and customs Máximo Laura’s childhood was steeped both in Andean lore and the practice of weaving textiles. Born in 1959, in Ayacucho, the capital of the ancient Wari Empire in the central highlands of Peru, Máximo Laura represents the family’s fifth generation of weavers.

Renowned for its finely woven and sophisticated abstract tapestries, the Wari Empire (500 to 900 CE) added its own influence to a style that began evolving 2,000–3,000 years ago, as evidenced by weavings preserved from the Paracas and Nazca cultures. As one society evolved into the next, culminating with the Inca (the last pre-Columbian culture), each one added its own ingredients to the bubbling brew of Peruvian folklore. This rich heritage managed to survive despite near obliteration by Spanish conquistadors.

Modern-day Ayacucho remains a celebrated center for traditional music and craft, particularly textiles. Máximo Laura remembers with childlike enthusiasm going with his mother to a major craft market to sell hand-woven rugs, bedcovers, and wall hangings when he was a young boy.

Maximo Laura’s home was a hive of cultural activity, much of it involving his father Don Miguel, a respected violinist and master weaver. Preparing the yarn for weaving was a constant endeavour that absorbed adults and children alike. Máximo Laura recalls how he and his siblings played around his father’s loom when they were small, observing every stage in the process of turning muddy scraps of wool gathered from the fields into yarn ready for weaving.

Sometimes the family would buy an entire fleece and his mother would prepare and spin the wool. “She would wash the skeins in small quantities at home,” he recalls. “If there was enough wool, we would go to the river several kilometers away and stay from morning until dark. By the end of the day, the wool was dry and we would return home. It was always an adventure to wash wool in the river.”

Gathered from sheep and alpacas, the local wool came in a variety of natural shades: white, black, beige, brown or a mixture of all. As the children grew— from the age of about six and up—it was a natural progression for them to help prepare the yarn, including coloring it with chemical or plant dyes. “Dyeing was almost a party for the children. We would crowd into the kitchen around the dye bath, which was made of old oil drums set on rocks over an open fire, burning wood or dried plants. We waited for the water to boil, and then helped prepare the dye, anxiously watching for the colors to appear.”

The children also helped warp the loom. “Wrapping the warp thread was almost a game. We learned to feed the threads, carefully knotting each one and getting the tension just right.”

The urge to innovate

Máximo Laura took command of the loom by the age of about ten. For him this was no longer play. This was about making a living, and he adopted his father’s work ethic, rising early to work his first weaving and finishing a saleable product before lunch—productivity Don Miguel rewarded with pocket money.

Máximo Laura’s first piece was a rectangular weave about 50 by 140 cm, a simple design with wide horizontal bands at the ends and a stylised Tiahuanaco (pre-Incan) figure in the center.

He carried on using that design and others like it for several years, learning every aspect of the weaver’s craft in his father’s workshop. Don Miguel always worked from the raw fleece—spinning, dyeing, weaving, and finishing. He produced functional items: rugs, blankets or bedcovers that would often be used in the fields. The items he sold were rarely bought with cash: they were paid for in materials or food. Nonetheless, his work was highly respected. Don Miguel was a master weaver, with his own apprentices and commissions, and his own style. Máximo Laura describes it as having a “rustic beauty,” using a limited palette and based chiefly from traditional designs such as the geometric shapes and animal motifs so often associated with Peruvian textiles.

While Máximo Laura was still at secondary school (age fourteen to fifteen), he began introducing new ideas to his father’s workshop—developing new color combinations, making small changes to the designs, and improving the quality of the weaving. However, by the time he left home in 1975 to study at the University of San Marcos in Lima, Máximo dreamed of becoming a writer or a poet and immersed himself in studying Hispanic literature, selling his weavings to pay his tuition.

When Máximo Laura was coming of age, Peru was embroiled in a cultural revolution marked by twenty years of bitter bloodshed. Beginning in 1980, the notorious battles between the Communist guerrilla insurgent group Shining Path ( Sendero Luminoso), the Túpac Amaru Revolutionary Movement (MRTA), and the government of Peru touched every corner of the country. Young Máximo Laura’s desire for self-expression found its voice within the threads of his loom.

Meeting Kela Cremaschi, an Argentinian textile artist, was pivotal to Máximo Laura’s career. As his teacher in Lima, she opened his eyes to the expressive potential of weaving as an art form. He devoured historical and anthropological accounts of Peru’s past and “collected” traditional Andean motifs found on everything from building facades to matchboxes.

So began what Máximo himself has characterised as an “obsessive, feverish” personal investigation of Andean designs and contemporary visual arts—inspiring the development of his own work—as well as consistent efforts to promote Andean design more widely.

Over the past thirty-five years, those explorations have ranged far and wide. Máximo Laura’s tapestries over that time have naturally reflected evolving centers of interest. What he himself sees as constants in his work are its rich and complex pictorial designs (some 2,500 at this stage, drawing often on legend and traditional spirituality), the variations in weave to build up multiple levels of texture, and the dramatic and sometimes explosive use of color.

The result is a highly individual personal style. Máximo Laura’s work appears very modern and far removed from the simpler craft weaves of his youth. Yet they incorporate the hand-weaving techniques, symbols, and spiritual concerns of Peruvian tradition.

Artistic meets spiritual integrity

At first glance, Máximo Laura seems to have rejected his cultural beginnings in Ayacucho and moved decisively into the modernist camp. But art is more than a brushstroke on a canvas or a thread on a loom: it demands ruthless self-realization. Finding his own artistic and spiritual path was part of the philosophy imparted by his father. It was an upbringing that Máximo Laura feels taught him to be “hardworking, responsible and passionate,” equipping him with a solid sense of tradition while giving him, license to develop his own voice as a contemporary artist.

Máximo Laura explains his sense that every one of us, whatever our walk of life, has an “exclusive responsibility” to be what he calls “children of this order, an expression of our time.” Through his art, he seeks to speak to a contemporary audience about contemporary issues, drawing on the worldview of his ancestors as one he feels remains valid for humanity today. His tapestries reflect a very personal attention to mankind’s interaction with the natural world that is highly topical today while evoking pre-Columbian beliefs about the tension between the physical and spiritual spheres: in opposition yet interconnected. His is a call, he says, for “balance, harmony, and spirituality.”

Traditional symbols and textile techniques give Máximo Laura a natural language for conveying these ideas. They are “inexhaustible” sources of inspiration. Máximo Laura says Andean traditions “are so powerful, such a timeless source, that it is hard to let go. I have tried to seek out new horizons, only to return to my past, my source, my origins.” But to be relevant to a twenty-first century public, age-old forms of expression need an aesthetic that spans the ages.

Máximo Laura’s distinctive tapestries, still woven by hand on traditional looms, speak to us in an ancient voice that has been uniquely translated for the contemporary world.

Learn more about Maximo Laura

Hand/Eye Magazine

Maximo Laura was recently designated as one of Peru’s Living Treasures, an honor worn easily by this self-taught artist whose textiles have received numerous …

Fiber Art Now Magazine

In many villages throughout Peru, time has stopped. Indigenous people proudly wear traditional clothing that identifies their specific region and community …

Textile Forum Magazine

The following text summarises the content of two conversations I had with Maximo Laura in Costa Rica between 10th and 13th September of this year …

Shop

Explore out catalog of Maximo Laura tapestries available for purchase. All tapestries in this catalog are …